- Home

- R. J. Anderson

Torch Page 15

Torch Read online

Page 15

The vast atrium at the tree’s center no longer awed Ivy as it once had, but it was a long way to the top, and there was no staircase. High above, faery girls spread their dragonfly wings and flitted from one floor to another, while the male faeries took bird-shape to do likewise. Light slanted through the windows, bathing the hollow trunk in light—and leaving no shadows for Ivy to hide in. Thorn could fly while keeping invisible, but Ivy couldn’t. And as Thorn had warned her, none of the Oakenfolk could become either a swift or a peregrine, so if any of the faeries spotted Ivy they’d know she was a stranger at once.

Well, she’d just have to move fast, then. Slipping past the faeries wandering in and out of the kitchens, library and other chambers at ground level, Ivy waited restlessly until the atrium above her stood empty. Then she dropped her invisibility spell, took swift-shape, and shot to the topmost level.

“Ow!” said an irritable voice, as Ivy landed and changed back. “You’re on my foot!”

Well, at least she didn’t have to wonder where Thorn had got to. Hastily Ivy stepped off and followed the grumbling faery through the arch to the queen’s chambers.

They’d only taken a few steps when Thorn stopped short, and Ivy nearly ran into her. “Blight,” the faery woman swore. “There’s a council meeting.”

Ivy was about to ask how she knew, since all the doors ahead of them were closed. But then she heard muffled sounds floating out from a door on the right.

Thorn whirled to escape, but Ivy grabbed her just as she turned invisible. “You can’t go yet!” she pleaded. “You have to take me to the queen!”

She must have spoken louder than she thought, because the door to the council room creaked open, and a short red-headed faery peered out. It was Periwinkle, the queen’s attendant—and one of the few Oakenfolk who knew Thorn’s secret.

“Wink!” Ivy whispered urgently. “It’s me, Ivy, and I’ve brought Thorn. We need to see Queen Valerian in private.”

The faery’s face brightened, and she hurried toward them. Thorn wilted, then shook Ivy off and turned visible as Wink grabbed both their arms.

“Don’t worry, I’ll hide you,” she promised. “This way.”

She led them to a serene, modestly furnished room, whose windows faced the nearby human house. Thorn thumped onto the sofa, her back to the view, while Wink led Ivy to one of the armchairs.

“I’ll tell the queen,” she said. “And don’t worry, Thorn. I won’t tell anyone else you’re here.”

Thorn wrapped an arm defensively across her belly. “You’d better not. Especially Timothy.”

Wink gave Thorn a reassuring smile and trotted off, shutting the door behind her. Ivy sat forward, about to ask Thorn what was wrong with Timothy in particular, but then she remembered—the boy was human, and Knife’s cousin by marriage. Some faery might have turned him small so he could visit the Oak, but what would he be doing in a council meeting?

It was tempting to ask, but the mulish expression on Thorn’s face warned Ivy against it. So she forced herself to sit back and wait until her anticipation turned to nervousness, then anxiety. Why hadn’t the queen come yet? Hadn’t Wink told her it was important? Or did she not care about making a treaty with Ivy’s people anymore?

Unable to bear it any longer, Ivy was about to get up when the door opened and Queen Valerian walked in. Simply dressed in a slate-colored robe, her hair crowned by a plain circlet and hanging loose down her back, she carried herself with a poise that Ivy would have envied if she weren’t so close to resenting it. Valerian certainly didn’t look as though she’d been in any hurry to get there, though Wink was quivering with excitement as she followed her mistress in.

“The queen wants to talk to Ivy alone,” she told Thorn. “You can come to my chamber, she’s dismissed the council so it’s safe, I’ll make you some tea—oh, it’s wonderful to see you!”

Thorn got up stiffly, frowning at Valerian. “Don’t you want my report?”

“I had one yesterday, from Broch,” said the queen. “He stopped by on his way to London. Be at peace, Thorn. Your presence alone tells me that this is no small matter, and Ivy can tell me the rest.”

Reluctantly Thorn followed Wink out, while the queen watched with a faint, tender smile. Then she turned to Ivy and said, “Are you thirsty? May I pour you some tea or berry wine?”

“That’s . . . kind of you, but no,” said Ivy, taken aback. Surely Wink or some other attendant ought to do that, not the faery queen herself. “Your Majesty, I’m sorry to interrupt your council, but I need your help.”

Valerian sat down, regarding her seriously. “What is your need, Ivy of the Delve?”

At once Ivy poured out her story. Judging by the queen’s expression, little of it surprised her, but she said nothing, even when Ivy was done.

“I’ve tried everything I could think of,” Ivy said, “but I realize now that I can’t do this on my own. You’re my only hope.” She clasped her hands together, imploring. “Is there anything you can show me, or give me, to help me save my people?”

Valerian considered this, her eyes thoughtful. Finally she said, “If I did, what would you offer in return?”

Warmth spread through Ivy. If the queen was willing to bargain, this gamble might work after all. “You want peace between our peoples,” she said quickly. “So do I. If you help, we’ll make a treaty with you. We’ll swear not to attack you or any faery under your protection for as long as you rule, if you promise to do the same for us.” She drew a deep breath. “And we’ll allow the faeries back into Cornwall.”

She’d rehearsed the speech as she lay awake last night, waiting for morning. Her people wouldn’t be happy to see the faeries return, not when their ancestors had fought so hard to get rid of them. But once they realized what Queen Valerian had done for them, they’d come around. They had to.

“You say ‘we,’” said the queen. “Have you discussed this with your followers?”

Ivy flushed. “Not yet.”

She’d meant to tell Martin and Mattock before she left, but she couldn’t find them. And she couldn’t risk telling Teasel and the other women in case they tried to stop her . . .

Or worse, got their hopes up, only to be disappointed all over again.

“So you speak to me as one queen to another,” said Valerian. “You believe it is your right to decide what is best for your people, whether they agree or not.”

Ivy shifted in her chair, uncomfortable. Did she have to put it that way? It made her sound like Betony. “I think they will agree,” she said carefully, “when they see how much healthier and better off they are. I—I never wanted to be Joan, or at least I didn’t think so, but . . . I don’t know how else to help them.”

The faery queen gave her a sympathetic look. “Leadership is a heavy burden,” she said. “Especially for one so young. And I can tell you have felt that weight keenly since your people left the Delve to join you. You have seen the ignorance of your subjects, their shortsightedness and resistance to change, their petty squabbles and misguided notions, and you have learned to guard your own counsel, as queens often must.”

Valerian rose and walked to the cupboard, taking out a bottle and two delicate, old-fashioned goblets. She poured the wine and crossed the floor to hand a cup to Ivy. “But tell me. What do you think changed your aunt from the good Joan she once was to the tyrant she is now?”

Ivy sank back in the armchair, staring into her cup. At last she said, “She’s always been strict, but she used to hear people out before she judged and treat them fairly. And now she doesn’t listen to anyone.” She shrugged helplessly. “I don’t know. Maybe it’s the poison affecting her.”

“Perhaps,” said Valerian. “But no one else has been driven mad by the poison, have they?”

No, they hadn’t. Not even Marigold, who’d been the first to feel its deadly effects, or Ivy’s father Flint, who’d endured the worst of it down in the diggings. They’d grown ill and even depressed, but not ruthless like Be

tony.

“Yet there is a poison that twists the mind,” the queen continued, taking her seat again, “and none of us is immune to it, not even the mightiest or most wise.” Her gaze held Ivy’s. “Fear.”

Ivy nearly laughed. With all the power she wielded, and a Jack strong enough to kill anyone who escaped her fire, what could Betony be afraid of?

“You may think me foolish,” said Valerian, “but I pity your aunt. She knows how to manage all the business of the Delve, but not how to cultivate her people. She can force the piskeys to obey her, but she cannot command their love. And the thought of change, especially the change you would bring, is abhorrent to her. Because to allow her people to leave the Delve, she would have to admit that she was wrong and you were right.” She gave a sad smile. “She is sick with fear, Ivy. Fear of losing her people and not being strong enough to save them.”

The words thudded like stones into Ivy. She’d never thought she and Betony had anything in common, until now.

“But . . . I don’t know how to help her,” Ivy said unevenly. “She won’t believe the poison is real, even with all the evidence in front of her, and she won’t let our people go. So what choice do I have? I can’t let her kill everyone I love, just because I’m afraid of becoming like her!”

Queen Valerian’s face softened. “No. That too would be a choice made from fear, not wisdom. But though she has done great evil and you are right to oppose her, your aunt was once a woman like you. And might be so again, if she can find the courage to repent.” She sipped her wine and gazed out the window pensively.

Ivy raised her own cup and drank, her thoughts tumbling about in confusion. Was the faery queen going to give her the help she needed, or not? She’d expected her to talk terms, not philosophy.

“I cannot teach you to conjure fire as Betony does,” said Valerian at last. “But I can show you this.” She rose and moved to Ivy, a ball of light coalescing on her palm. “Take it from me, if you can.”

This must be the spell-fire Thorn had mentioned. Hesitantly Ivy cupped her hand to the globe, feeling its sizzling energy against her skin. It rolled off the queen’s fingers onto hers, and Ivy’s heart leaped—but as soon as Valerian withdrew her hand, the glow winked out.

“Again,” said the faery queen, drawing up a chair next to her. “Focus, and try to keep it alight.”

Ivy concentrated, trying to feel the queen’s power flowing into the spell and make her own power match it. But though she tried until sweat prickled her hairline, the magic always vanished as soon as Valerian let go.

“I can’t!” Ivy burst out, slapping the arm of the chair. “I don’t know what’s wrong with me!”

The queen laid a comforting hand on her shoulder. “Don’t blame yourself,” she said. “Many faeries find spell-fire difficult or impossible. And I know little of piskey magic, so I may not be the best teacher for you.”

Perhaps, but if the queen of the faeries couldn’t teach her, who could? “Are there any other spells I could use?” Ivy asked, without much hope.

“If you were fighting a different enemy, perhaps. But the fire your Joan wields burns hotter than any I have ever known. And if your own mother could spend six years fighting in the Empress’s army, yet still be too weak to resist her . . .” She spread her hands. “I dare not give you false hope, Ivy. Even spell-fire would be a feeble weapon against Betony’s dark magic, and I know no spell that will keep her from killing you.”

Ivy bit her lip. Deep down she’d known it would come to this, however fervently she’d hoped otherwise. “Then . . . will you give me an army?”

The queen gazed at Ivy with pity. Then, sadly, she shook her head.

“Please,” Ivy blurted in mounting panic, “it’s our only chance. Your people fought the Empress, they’re better trained than any piskey in the Delve—”

“Yet they are faeries,” said the queen, “and under my protection. Much as I wish for peace, I will not buy it that way. The cost is too high.”

She’d known faeries could drive hard bargains, but Ivy had only one thing left to offer. “We’ll pay whatever you want,” she said hoarsely. “My ancestors could find gemstones and precious metals anywhere—they made beautiful things, like you’ve never seen. Your soldiers can take as much treasure as they like from the Delve, and every year we’ll send more. Please.”

“Ivy.” Valerian spoke softly, but her voice was firm. “You are not the first to offer me wealth in exchange for soldiers. Martin promised me all his father’s hoard if I would bring my army into Cornwall, depose your aunt, and crown you in her place. But my people suffered too much at the hands of the Empress for me to force them into another battle, especially one they have no stake in. What prize can you offer that is worth even one drop of faery blood?”

Ivy clutched her wine cup, shaken. So Martin had tried to make the same bargain when he was here? He’d really been willing to give up everything he owned, for her?

“And my help would cost you more than you realize,” the queen continued. “If I lent you my army, it would be my power you wielded, not your own. You might claim to have freed your people, but would they believe it? Would they not see you as a puppet Joan under my control?”

It was true, Ivy realized, heart sinking. With an army of faeries she might defeat Betony and Gossan, but her rule over the Delve would be short-lived. Her people would never fully trust her, and the moment some other piskey-woman proved she could make fire, they’d lose no time in overthrowing Ivy and setting up a new Joan in her place. Then all hope of peace between the piskeys and the faeries—let alone the spriggans—would be lost.

“Then I’ll step down,” Ivy said, heavy with defeat. “As soon as Betony’s out of the way. I’ll let my people choose anyone they want to lead them, and I won’t interfere. But if you don’t help us. . .” Her throat closed up, grief choking her. She finished in a whisper, “Then the piskeys of Kernow will die.”

“Even the stars will not last forever,” said Valerian. “But whether the end has come for your people, I cannot say. And neither can you, though their need is great and all your hopes seem fruitless.” She laid her hand over Ivy’s. “There are powers greater than magic or strength of arms. And if you know you have nothing, you have more than you know.”

She meant it as comfort, no doubt, but it sounded like so much rubble to Ivy. Fighting bitterness, she pushed herself to her feet.

“I’m sorry to have disturbed you, Your Majesty. I’ll go now.”

There was no use staying in the Oak any longer. If Queen Valerian wouldn’t help Ivy, certainly no one else would. Feeling hollow, Ivy walked down the hallway, trying to remember which of the doors was Wink’s.

“Thorn!” she called, hoping the faery woman could hear. “It’s time to—oh!”

The door across from Ivy had opened, but it wasn’t Wink looking at her. It was Linden, the queen’s youngest attendant. And behind her, alert and curious, sat two others: Rhosmari, Broch’s fellow countrywoman from the Green Isles. . . and the human boy Timothy.

Silently Ivy berated herself. She’d thought they’d all left when the queen dismissed her council. “Never mind,” she said hastily, trying to pull the door shut, but Timothy had already leaped to his feet.

“I knew it! She’s here, isn’t she?” He pushed past Linden, dodging Ivy’s attempt to block him, and set off down the hallway. “Thorn!”

A muffled oath came from the door nearest the landing—Thorn remembering she couldn’t leap away, no doubt. Ivy raced after Timothy and flung herself in front of him. “Don’t go in.”

The human boy wasn’t much older than Ivy, but he was a head taller, and it would have been easy for him to push her aside. Yet he stopped. “Why not?”

“Because . . .” Ivy cast about for an answer that would satisfy him. “She doesn’t want to talk to anyone. And we have to leave right away.”

Timothy looked crestfallen. “Really? That’s too bad. I was hoping to find out how she was doing, so I

could tell Peri—I mean Knife. She’s been worried.”

“She’s fine,” Ivy assured him. “Please tell Knife there’s nothing to worry about.”

“If you say so.” Timothy heaved a sigh, then added more loudly, “Take care, Thorn. I’ll see you.”

That wasn’t so hard, Ivy thought with relief, as the human boy turned away. But then a wicked smile curled his mouth, and before Ivy could stop him he lunged past and flung the door open. “Boo!”

Thorn stood silhouetted against the light of the windows, while Wink struggled to help her into her jacket. For an instant both faeries froze, gaping at Timothy. Then Thorn thrust her arm down the remaining sleeve, strode forward, and drove her fist into the boy’s stomach.

He doubled over, wheezing, as Thorn glared at him. “Meddlesome brat,” she growled. Then she flung her coat closed, though it didn’t quite meet over her belly, and stamped off to the landing.

A pained silence followed, while Timothy staggered about clutching his stomach. Then Rhosmari exclaimed, “Ivy!” and rushed to greet her with a warmth that took her by surprise. “I’m so glad to see you. How is Martin?”

“Ouch,” said Timothy plaintively, but Rhosmari shook her head at him.

“You should know better than to cross Thorn by now. And pretending to be jealous of Martin won’t make me feel any more sorry for you.”

Ivy liked the Welsh girl, all the more since she’d seen Martin’s memories of the time they’d spent traveling together. And both Linden and Wink had been kind when Ivy first came to the Oak. But Ivy couldn’t bear to talk to them any longer.

“I—I can’t,” she stammered, backing away to the landing. “I’m sorry.” Then she changed to a swift, and fled.

“Blighted boy can’t keep his nose out of anything,” Thorn fumed when Ivy caught up to her in the hedge tunnel. “And the queen doesn’t even try to stop him—you don’t think he noticed, do you?”

He might not have, if Thorn hadn’t reacted so spectacularly. But there was no point in saying that now. “I don’t know.”

Quicksilver

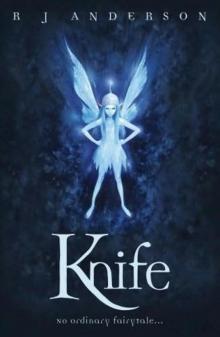

Quicksilver Knife

Knife Arrow

Arrow Ultraviolet

Ultraviolet Wayfarer

Wayfarer A Little Taste of Poison

A Little Taste of Poison Nomad

Nomad Torch

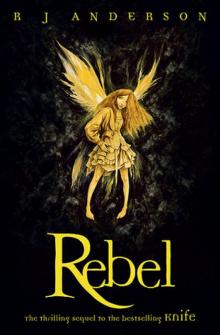

Torch Rebel fr-2

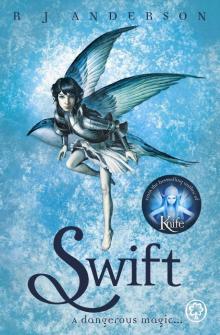

Rebel fr-2 Swift

Swift Faery Rebels

Faery Rebels Spell Hunter fr-1

Spell Hunter fr-1