- Home

- R. J. Anderson

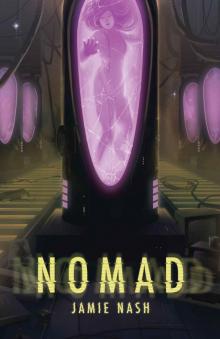

Nomad

Nomad Read online

Acclaim for

NOMAD

“Nomad is gripping and full of surprises. R.J. Anderson’s writing drew me into her fantastic storyworld and kept me glued to the page. Teen fantasy fans will devour this magical adventure. Good thing book three is coming soon. I’ll be first in line to finish Ivy and Martin’s story.”

— Jill Williamson, award-winning author of the Blood of Kings trilogy and The Kinsman Chronicles

“Nomad, the second book in R.J. Anderson's lyrical The Flight and Flame Trilogy, is an adventure that will have you flying high and digging deep, unearthing stunning revelations alongside our heroic piskey, and remembering again that courage is contagious. I truly love these books!”

— Shannon Dittemore, author of Winter, White and Wicked

“As a sequel, Nomad soars, carrying readers on an adventure even more perilous and spellbinding than the first. Once again, Anderson crafts an immersive and fascinating storyworld steeped in faery lore, anchored by a plucky, down-to-earth heroine you can’t help but love!”

— Gillian Bronte Adams, author of The Songkeeper Chronicles

“Powerful fantasy with excellent world building and compelling characters.”

— Peters Gazette

Books by R.J. Anderson

No Ordinary Fairy Tale Series

Knife

Rebel

Arrow

Uncommon Magic Series

A Pocket Full of Murder

A Little Taste of Poison

Ultraviolet Series

Ultraviolet

Quicksilver

The Flight and Flame Trilogy

Swift

Nomad

Torch

Nomad

Copyright © 2014, 2020 by R.J. Anderson

First published in the UK by Orchard Books (a division of Hachette), London

Quotations from The Peregrine are reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. © 1967 J. A. Baker.

Published by Enclave Publishing, an imprint of Third Day Books, LLC

Phoenix, Arizona, USA.

www.enclavepublishing.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, digitally stored, or transmitted in any form without written permission from Third Day Books, LLC.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to actual people, organizations, and/or events is purely coincidental.

ISBN: 978-1-62184-141-8 (hardback)

ISBN: 978-1-62184-143-2 (printed softcover)

ISBN: 978-1-62184-142-5 (ebook)

Cover design by Kirk DouPonce, www.DogEaredDesign.com

Interior design and typesetting by Jamie Foley

To Simon, who helped me get it right.

Table of Contents

Cover

Acclaim for Nomad

Half-Title

Books by R.J. Anderson

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part Two

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Available Now!

For a bird, there are only two sorts of bird:

their own sort, and those that are dangerous.

No others exist. The rest are just harmless objects,

like stones, or trees, or men when they are dead.

— J. A. Baker, The Peregrine

“Knockers! The knockers are coming!”

The shout rang through the fogou, echoing off the rocky walls of the tunnel and into the chambers beyond. The boy had been drowsing, curled on the earthen floor beside his clan-brothers; now he was shocked awake as his father seized his elbow and wrenched him to his feet.

“Take this and hide it,” he commanded, and the boy staggered beneath the unexpected burden of a sack almost as heavy as he was. As he floundered for a better grip, a coin tumbled out of the bag’s mouth and rolled across the floor. Instinctively the boy stooped to retrieve it.

“Leave it,” his father snapped, spinning him around and giving him a shove. “Get out of here! Quick!”

The boy knew better than to hesitate. He clutched the sack to his thin chest and stumbled for the exit. Around him rose shouts and curses, the rasp of knives and the clatter of spears as the men of the clan raced to arm themselves. And from the hillside above, distant but growing louder, came the jeering war cries of the enemy.

Mother, the boy thought, sick with dismay. She told them where to find us. Father was right.

But he had no time for regrets, even if it was his own foolishness that had brought this disaster upon them. His father had entrusted him with the treasure, and it was his duty to keep it safe. The boy gripped the sack tighter, and ran.

As he burst out of the fogou, scrambling up the steep, overgrown bank that hid the underground passage from view, the first light of dawn was greying the horizon. In the tunnel it had been damp but sheltered; here the cold wind slashed through his ragged tunic and raked at his bare legs. He glanced wildly in all directions, wondering where in this scrub-dotted wilderness he could hide.

The carn! It stood on the ridge to the northwest, a lopsided heap of stones. If he crouched low and moved quickly, he might reach its shelter before daylight robbed him of what little concealment he had. But did he dare to make a run across the open valley? Or would that be his last mistake?

He had only a few heartbeats to decide. A ragged line of knockers were tramping down the hillside—fifteen of them, stocky and muscular, with steely breastplates glinting beneath their cloaks. Some were armed with thunder-axes, the magical hammers they used for deep mining; others wore long knives at their hips, or carried staffs stout enough to crack a man’s skull with one blow. But he saw no bows or slings among them—nothing that could hurt him at this distance. Tightening his grip on the sack, the boy bolted for the carn.

Don’t look back, he told himself, panting as his feet slapped the crumbling earth and the sack bumped against his spine. You can’t help Father and the others now.

He knew what they’d be planning, because it was the only strategy that made sense. They hadn’t a chance of defeating so many knockers in the open: not with only four seasoned fighters, a one-legged cook, an old healer, and a handful of striplings who’d scarcely earned their names. Besides, they wouldn’t risk leaving the women undefended. So they’d lure the knockers into the fogou, where the dark and narrow passages would give them the advantage. They’d use their luck-magic to make their enemies trip and blunder; they’d whistle up a wind through the tunnel and blow dust in their eyes. Then they’d drop low and slash the knockers’ hamstrings, or duck behind them and slit their throats. It was a filthy way to fight, but the boy’s people were outcasts anyway, so they had no honor to lose… and as his father always said, better a live dog than a dead lion.

He’d almost reached the carn now, stones skittering beneath his feet as he fought his way up the hill to

its summit. The stone pillar looked crude but was cunningly built, ancient already when his grandsire was born and one of the many secret places where his people had found refuge in the long years of their persecution. To strangers it would appear a solid heap, but the boy knew how to make the carn give up its secrets. He scrambled to the base of the pile, crouched and pressed his small white hand against a certain stone.

With a grating rasp the carn opened, rocks shifting and rearranging to form a low doorway. The boy crawled into the darkness, pulling the sack after him, and nearly fell headlong down the stairs. Catching himself, he conjured a glow-spell and crept downward, the magical light bobbing like a will-o’-the-wisp before him.

At the foot of the staircase a chamber opened, rough and bare. It was even darker than the fogou, and dank-smelling too: a forbidding place, with nothing comfortable about it. But in the middle of the floor, on a rough dais of stone, stood a crock piled to the rim with treasure. Coins and goblets and plates of gold and silver, rings and brooches and jeweled pendants, with weapons and armor piled haphazardly to either side. Ancient riches forgotten by the long-dead men and women who had owned them, they belonged to his people now, as much as they belonged to anyone.

The boy hesitated, awed by the presence of so much wealth. With reverent care he approached the dais, upended his sack and let its contents spill onto the hoard. Then he backed out of the chamber. This place was not for him, not yet.

Hurrying back up the stairs, he extinguished his glow-spell and was turning to shut the carn when the air split with a thunderous crack and the ground beneath him shuddered. The boy staggered, lost his footing and fell. As he picked himself up, wincing at fresh cuts and bruises, shouts of triumph rose from the valley below.

The knockers had discovered the fogou. But instead of plunging inside to do battle, they’d split into two parties and surrounded both ends of the tunnel. And between them a fresh cleft in the earth gaped like a mortal wound, while the knocker who’d made it hefted his thunder-axe and braced his stout legs for another swing.

They were cracking the fogou apart from the outside. Shattering the stone slabs that formed the tunnel’s ceiling, and bringing them down on the men and women trapped within. The boy’s fists clenched, helpless rage storming inside him. If only he were bigger, stronger, more skilled at luck-magic or wind-working…

But along with cunning he had also learned caution, and he knew better than to charge into a fight he could not win. Though his stomach knotted and his eyes burned, he stayed motionless as the thunder-axe smashed down for the second time, and with a roar and a rumble the whole fogou collapsed.

The boy spun away, shoving his bloody knuckles against his mouth to keep from crying out. He did not want to see what the knockers did next, how they searched the rubble for his people’s bodies and finished off any living ones they found. The Grey Man and Helm, Dirk and Ram and their wives, Spit the cook and Needle the healer, Dart and Parry and the other boys—all of them were dead, or soon would be.

And it was his fault.

Ivy bolted upright, gasping into the darkness. Her cheeks felt wet, and her insides roiled with the horror of what she’d just seen. For a few wild seconds she couldn’t tell where she was, or even who she was: part of her was still back on that rugged hillside with the boy, sharing his agony and shame. But then her night-vision focused, revealing the rocky walls around her and the firelight glowing at the mouth of the cave, and she collapsed onto her bed of ferns in relief.

It was a dream, she told herself. Only a dream.

Yet the assurance rang hollow, no matter how many times she repeated it. It hadn’t felt like an ordinary nightmare: it had been too vivid for that, too powerfully real…

“Ivy! What’s wrong?”

In an instant Martin was beside her, helping her sit up and move closer to their small fire. The lithe strength of his arm around her shoulders should have comforted her, but Ivy’s nerves were raw and she couldn’t bear it. She squirmed away.

“I’m fine,” she panted. “Just—”

But words failed her. She needed time to breathe, to think, before she could explain.

Martin sat back on his heels and watched her. The firelight gilded one high cheekbone and made his pale hair shine silver, and for a moment he looked as haughty and remote as a faery prince of legend. Then he turned to toss another stick onto the flames and the spriggan in him leapt out—glittering eyes, sharp features and teeth bared in a mirthless smile. “Fine, you say. And I thought piskeys couldn’t lie.”

Ordinarily Ivy would have been indignant, but she hadn’t the will to argue with him, not now. “I’m not hurt, or sick, or in danger,” she said. “I had a bad dream, that’s all.”

Martin raised his brows at her, and all at once Ivy was conscious of her own tear-streaked face and tangled hair. She shifted back against the rocky wall, hugging her elbows for warmth. “I thought you’d gone hunting,” she said. “I didn’t expect you back until morning.”

“It’s almost that now,” said Martin. He poked the fire until it collapsed into a glowing heap, and a few sparks flitted up to snuff themselves on the ceiling. “But you can lie down again if you like. It’s not as though we’re in a hurry.”

He sounded indifferent, but his back was stiff, and Ivy wondered if she’d hurt him. “Martin…”

He waved her aside. “You don’t need to explain. I understand.”

Ivy was bewildered—how could he, unless he was reading her mind? But then another possibility dawned on her. It would explain why he’d flown off in bird-shape every night they’d been traveling together, and left her to sleep by their campfire alone…

“Oh,” she said softly. “Do you have bad dreams, too?”

“Me? No.” He flicked her an odd look. “I don’t dream at all. I never have, for as long as I can remember.”

“Then what are you talking about?”

Martin sighed and sat down, folding his legs beneath him. “I know you wanted to travel together,” he said, “and in the beginning, it seemed like a good idea. But we’ve been tramping over the countryside for days and we haven’t found a single spriggan, or even a clue to tell us where they might have gone. And you haven’t learned anything that would help you convince your queen—or rather, your Joan—that you’re not a traitor.”

I banish you from the Delve, now and forever. Betony’s cold words echoed in Ivy’s mind. Go where you want and call yourself what you will, but you are no longer a piskey.

Ivy shook off the memory. She might be half faery, but she would always be a piskey at heart, no matter what her aunt said.

“Only because I’m not sure what I’m looking for,” she replied. “It could be… I don’t know, a better place for our people to live. Another mine that’s just as secure as the one we’re in now, but isn’t contaminated with poison. Or maybe all we need is proof that the spriggans and faeries aren’t a threat to us anymore, and it’s safe to live on the surface again. I’ll know when I find it. But I’m not ready to give up yet.”

“You don’t want to give up,” countered Martin. “Because you’re loyal, and stubborn, and you don’t know when to quit. But you’re not made for this life, Ivy. And it’s making you miserable.”

“This life.” She spoke flatly, fighting to control her anger. “What do you mean by that? You think I’m too weak or frightened to keep up with you?”

“Ivy…”

“I was the one who found you chained up at the bottom of the Delve, remember? I climbed down the Great Shaft night after night to bring you food and water and listen to you gabble lines from Shakespeare, when for all I knew you might be planning to eat me alive. I was the one who convinced you to teach me bird-shape, and then I risked my life to set you free—”

Martin cut her off with an impatient gesture. “You’re not listening. I don’t doubt your bravery. Or your strength.”

“Then what are you talking about?”

“This.” He drew his thumb down he

r wet cheek. Ivy’s heart jumped, and she flinched away.

“You’re a piskey,” Martin said. “And I’m a spriggan. I’d never even heard that word until you accused me of being one, but I’ve learned enough now to understand.” He let his hand drop and sat back. “You’re afraid of me, however you try to deny it. And you should be.”

“I’m not.” She tried to sound confident, but her voice came out squeaky, like a little girl’s. Like the child she’d been on the night the spriggans took her mother…

Except they hadn’t taken Marigold, not really. Her mother had been captured by the evil faery Empress instead, and spent the next six years struggling to escape and get a message to her family. Until Martin came to tell her Marigold was alive, Ivy had believed that spriggans were ravening monsters responsible for all the evil in the world. But now she knew that magical folk weren’t so easily divided into tribes of good and bad as that.

“I’m not afraid,” she said, louder this time. “I know you would never hurt me. You saved my life.”

Twice, in fact. And though the healings Martin had performed on Ivy had drawn the two of them together and changed them both in ways she was still struggling to understand, she was almost certain he hadn’t meant that to happen. It wasn’t in Martin’s nature to bind himself willingly to anyone.

“But you are afraid of spriggans,” he said. “Other spriggans, I mean. You’re willing to help me search for them, but you don’t really want to find them. Not after all the terrible things they did to your people.” He picked up a twig and twirled it between his fingers, transforming it to a knife and back again. “No wonder you’re having nightmares.”

Was he trying to frighten her away? If so, he’d be disappointed. Ivy got up restlessly and paced to the mouth of the cave. “It’s not what your people did to mine,” she said, rubbing her arms as the breeze cut through her light sweater. “It’s more what my people did to them.”

“What do you mean?”

The suspicion had been growing in Ivy for days now, as she and Martin hunted through seaside caves, old ruins and rock formations without finding the slightest trace of the spriggans’ existence. The piskeys of the Delve might live quietly these days, but little more than a century ago Ivy’s knocker forebears had roamed the countryside in small armies, killing or enslaving any magical folk who dared to resist them. Ivy’s own mother and grandmother had been captured in a raid on a faery wyld, and Ivy wasn’t the only piskey with faery blood in her, not by a long shaft.

Quicksilver

Quicksilver Knife

Knife Arrow

Arrow Ultraviolet

Ultraviolet Wayfarer

Wayfarer A Little Taste of Poison

A Little Taste of Poison Nomad

Nomad Torch

Torch Rebel fr-2

Rebel fr-2 Swift

Swift Faery Rebels

Faery Rebels Spell Hunter fr-1

Spell Hunter fr-1