- Home

- R. J. Anderson

Torch Page 14

Torch Read online

Page 14

“If all goes well, I’ll be back by tomorrow. If not . . .” Broch gave an apologetic shrug. “It might be another day. Or more.”

Thorn made a face at that, but she didn’t argue. David Menadue had agreed to help Broch and even give him a place to stay, so there was no need for her to worry.

“I’ll get the treasure,” said Martin, and slipped out to the main cavern. Mattock sat quietly a moment, not looking at Ivy, then got up and left without saying a word.

Maybe he was trying to think of a plan—or at least Ivy hoped so. Because much as attempting to rescue her men frightened her, telling their families she’d given up would be worse. She studied the barrel, picking at a splinter, until a series of jingling footsteps told her Martin had returned.

“Here you go,” he said, swinging a leather pack off his arm and handing it to Broch, who staggered and nearly dropped it. He cast Martin a startled look.

“Too heavy?” Martin asked mildly.

“Almost, but I’ll get used to it.” Broch turned to Ivy. “Any message for your mother?”

She’d probably rung the house at least once and wondered why no one answered. “Tell her I’m fine,” Ivy said. “And that Cicely’s . . .” She hesitated. “Helping Mica. And I hope to see her soon.”

Broch hefted the pack and went out. Thorn followed, leaving Ivy and Martin alone.

“That evasion was positively faery-like,” said Martin, pressing a hand to his heart. “You’ve come so far. I’m proud.”

Ivy gritted her teeth in exasperation. Martin had visited the main cavern only once last night, to say a few quiet words to Mattock. But his gaze had held Ivy’s all the while, and she’d felt his longing as keenly as her own. Yet now they finally had a moment together, he seemed to be pushing her away. “Are you trying to irritate me?” she asked. “This isn’t a joke, Martin.”

His expression sobered. “No. But Ivy, you need to think—”

A child’s shriek rang out from the main cavern, followed by pattering footsteps and the sound of hysterical weeping. Anxious, Ivy started toward it, only to stop short as Mattock strode through the doorway, dragging a wildly kicking Dagger behind him.

“Let go, you piskey oaf!” the spriggan boy snarled. “Get your dirty paws off me!”

Martin’s jaw tightened. “Let him go, Matt.”

Mattock dropped the boy and stepped back, folding his arms. “He tried to grab the treasure from Broch,” he said flatly. “And when Thorn gave him a clout on the ear for his trouble, he blawed up like a quilkin and scared Thrift out of her wits.”

Martin cast a bemused look at Ivy. “Blawed up . . . ?”

“Puffed up like a frog,” Ivy told him. “Whatever that’s supposed to—” She bit off a startled oath as Dagger’s face swelled to monstrosity, his thin body erupting into the stumpy, misshapen form that spriggans used to frighten enemies away. She’d seen it in one of Martin’s childhood memories, but she’d never expected to witness it with her own eyes.

Martin’s hand whipped out, seizing Dagger by the ear, and the boy yelped and deflated. “Like the toad, ugly and venomous,” Martin said coldly. “What do you think you’re doing, you wretched little imp?”

“You’re no spriggan!” the boy spat, eyes filling with angry tears. “The Gray Man would be shamed o’ you. Filling up our barrow with knocker folk and giving away our treasure—”

“I’m shocked to hear you disapprove,” Martin said drily. “You’ve been so subtle about it.” He whisked a handkerchief from his pocket and tossed it to the boy, then turned to Ivy and Mattock. “If you’ll excuse us, we have business to settle.” Without waiting for an answer, he put a firm hand on Dagger’s shoulder and steered him through the inner door.

Mattock turned to leave, but Ivy blocked him. “Don’t you have any idea how to help the others? Think about Quartz, and Elvar—they’re just boys! There has to be some way we can get them back from Betony.” She pushed her hands through her curls, gripping them in frustration. “Think, Matt! I can’t do this without my Jack.”

Mattock flinched like she’d whipped him. “I’m not the Jack you need,” he said, his voice low and rough. “I’m nobody’s Jack now. And I can’t help you. No matter how I wish I could.”

Then he pushed past Ivy and walked out, leaving her alone.

Ivy lay on her bedroll, staring at the ceiling of the main cavern. Not that there was anything to look at: with all the glow-spells extinguished, the barrow was black as any mineshaft. But she couldn’t sleep.

It wasn’t that the rest of the day had gone poorly—quite the opposite. Apart from Dagger’s outburst, there’d been no squabbles between the piskeys and the spriggans at all. And though Martin’s elusiveness frustrated her, she understood now why he was doing it. He knew how fearful her people were of spriggan tricks, and he didn’t want to give them any reason to doubt Ivy’s judgment.

Yet in his subtle way, Martin had made a powerful impact on the piskeys. When they followed Ivy to the barrow they’d expected a grudging welcome at best, followed by an interrogation—or worse, bewitchment. But Martin had retreated, and sent the children to serve the piskeys dinner instead.

The choice had been calculated, but there’d been nothing dishonest about it. He’d let all his charges behave according to their nature, from Pearl’s shy eagerness to Dagger’s resentment, knowing Ivy’s people would see that honesty and be reassured by it in a way no pretense could do. Without a word he’d disarmed the piskeys’ fears and left them doubting everything they thought they knew about spriggans.

But Clover’s youngest son had sobbed himself to sleep tonight, missing his father, and Daisy’s eyes still welled up at every mention of Gem. Ivy’s followers might be safe here, but they’d never be happy.

Ivy had lain awake for what felt like hours when the door to the adjoining room opened and a sliver of light shot out. Fern appeared in the doorway, beckoning furtively, and with a soft rustle three more women got up and padded to join her, as though they’d been waiting for her signal.

None of them had said anything to Ivy about a meeting. If the other women were plotting behind her back, she had better know about it. Turning invisible, Ivy jumped up and sprinted after them, slipping through just before the door shut.

What she found on the other side, to her surprise, was a cozy nest of sacks and blankets on the floor, and Fern pulling the cork from a wine jug. She sniffed it, took a tentative sip and then a bigger one before passing the jug to Teasel and sitting down next to her. “Well,” she declared, leaning back, “this is more like it.”

“Proper job, that wine is,” said Teasel, wiping her mouth. “Where’d you find it?”

“Oh, I’ve been poking about,” Fern told her. “Mattock showed me practically the whole place, when that spriggan fellow and his boys were out fishing. It’s not the Delve to be sure, but it’s a fine big barrow, and there’s a whole crate of wine jugs in one of the storerooms. I thought with so many children about, who’d miss it?”

They fell into a comfortable silence while the jug made its way around the circle. At last Moss cleared her throat. “So, Teasel, what’s on your mind? I like a drop as much as any piskey, but you’ve not called us here for that, I’m sure.”

The older woman sat up, smoothing her skirts briskly. “Ayes, you’re right. Truth is, I’ve been thinking of Ivy. I’ve been watching her and the spriggan since we got here, but I don’t see much sign of her being bewitched, do you? And it puts me in mind of a story the aunties used to tell in secret, when I was a young maid—”

“Ah, you mean ‘The Spriggan Lover.’” Old Bramble grinned, eyes twinkling wickedly. “I got a right wallop when my mam caught me listening to that one!”

Fern pursed her lips disapprovingly, but she didn’t look surprised, and neither did Moss. Whatever the story was, it seemed to be well known by the older women.

“The thing is,” Teasel continued, “we thought ’twas only folly, imagining love could make a monster into

a man. And the droll-tellers made so much of spriggans being all wicked, telling us we daren’t go out on the surface for fear of them, we never dreamed it could be otherwise. But what if it weren’t just an old aunties’ tale? What if it really happened, long ago?”

“There’s no happy ending to that story,” Fern said darkly. “At least as it was told me. The piskey-girl’s brothers caught the spriggan and flung him down a mineshaft, and she died of a broken heart.”

“But they had a grand love first,” Moss murmured, then caught Fern’s glare and took a hasty swig of wine.

“And that’s the point, isn’t it?” Teasel said. “Not how it ended, but that such a thing could happen. And might not have ended badly either, if her folk hadn’t been so hard against it.”

“You’ve not made your point yet, by the look of you.” Fern took the jug from Moss, her jaw set. “Out with it, then. I’m not afraid of plain talking.”

Teasel gave her a sympathetic look. “Your Mattock’s a fine boy, Fern. We’d have been glad to crown him our Jack, if Gossan hadn’t served him so badly. But for all they’ve been tiptoeing around each other, it’s clear Ivy’s in love with that spriggan, and he with her. So maybe . . .” Her gaze travelled the circle. “Maybe we should stop holding her to a promise her heart can’t keep.”

Fern bristled. “So you think Matt’s not fit to be her husband? And some—some pinch-faced slip of a spriggan is?”

“I’m not talking of what ought to be,” Teasel said gently. “Only how things are. And wouldn’t it be better for Matt to find a wife who can love him with all her heart, instead of waiting on Ivy to make him a corner in hers?”

That silenced Fern. She ran her thumb around the lip of the jug, her mouth lined with unhappiness.

“The thing is,” Teasel continued, “we’ve all been looking to Ivy to save us, and no one can say she hasn’t tried. If it weren’t for her we’d never have known about the Delve being poisoned, let alone have a chance to come out of it. But Betony’s got our men, so we have to go back and face her. And if she’s got fire and Ivy doesn’t . . . there’s only one way that story’s going to end.”

“Like Jenny’s did,” said Moss huskily, and the other women looked grave.

“Betony doesn’t want Ivy, anyhow,” Bramble pointed out. “She banished her, like she did her mother.”

“That’s right,” Teasel said. “It’s us she wants.” She motioned for the wine jug, and reluctantly Fern gave it back.

“So what you’re saying is we wait another day or two and then take ourselves back to the Delve, us and Daisy and Clover and Matt and all, and leave Ivy with her spriggan fellow.”

“Ayes.” Hew’s wife wiped her mouth and set the jug aside. “That’s what I’m saying. But someone’s got to break it to Ivy and make sure she doesn’t chase after us and throw her life away. We wanted a new Joan so badly, we talked ourselves into thinking she could save us. But now we know she can’t, it’s high time we stopped asking her to try.”

Ivy shut her eyes, hot tears streaking her cheeks. There was nothing behind their conspiracy but kindness, but it hurt to be reminded how cruelly she’d disappointed these women, and how little faith they had left in her now.

Still, they were offering Ivy a way out, and part of her longed to take it. But how could she be happy staying with Martin while her people sickened and died under Betony’s rule? If she did nothing, she’d soon be the last of the piskeys—and this time there’d be no prophecy and no magic to save her people from extinction.

She couldn’t let that happen. There had to be another way.

Please, help me, she prayed silently. I’m alone and helpless, and I don’t know what to do. Then she bowed her head and sat motionless until the older women finished off the jug of wine and went away.

But though Ivy waited, no answer came, and a coil of bitterness tightened around her heart. Maybe there was no higher being who cared about piskeys anymore, if there ever had been. Maybe the Shaper or the Great Gardener or whoever it was had given up on Ivy’s people when they wiped out the spriggans, and now they were on their own.

But as she tossed atop her bedroll, desperate to sleep, she suddenly remembered what Martin had said that morning.

One is to find a spell that will stop Betony’s fire.

The other is to raise an army.

Ivy sat up, wide awake. Then she kindled her skin-glow and scrambled out of bed to find Thorn.

“No,” Thorn said crossly. “Absolutely not.”

She’d refused to answer last night, no matter how Ivy pleaded: she’d pulled the blankets over her head and curled up like a furious snail until Ivy gave up and went away. So she’d coaxed Thorn outside for a walk after breakfast, but the faery woman still wasn’t cooperating. “I’m not taking you to the Oak. If you want to see Queen Valerian, ask Broch when he gets back.”

“I can’t wait that long,” Ivy protested. “He could be gone for days. Anyway, isn’t this why the queen sent you and Broch to Cornwall—to make peace between your people and mine? I know you don’t want anyone to find out about the baby, but doesn’t duty come first?”

The wind whipped Thorn’s hair into her eyes, and she swiped it back with a scowl. “Your idea of peace seems to involve a lot of fighting. And you’re standing on a thin twig with your talk of duty, too.”

Yet she hadn’t turned back to the barrow, even though the breeze was chilly and they could both see their breath. Determined, Ivy pressed on. “There might not have to be a battle, if Queen Valerian can teach me more magic. She’s the queen of all the faeries, isn’t she? So she must be at least as powerful as my aunt is. Are you sure she can’t make fire?”

Thorn made an impatient gesture, and the grass between them burst into flames. Ivy jumped back, then realized it was only illusion: the fire looked real, but it wasn’t burning anything at all. She stooped to touch it and felt no pain, only a gentle heat.

“Glamour,” Thorn said. “That’s all. It doesn’t even warm you really, it’s just a trick of the mind.” She waved her hand again, and the illusion vanished. “If I can do that, of course the queen can. But I can’t see how it’s going to help you.”

Ivy pointed at the grass, concentrating. But no matter how hard she wished nothing happened, so at last she let her hand drop. Besides, Thorn was right. What good would mere pretend fire be against the woman who’d burned Jenny and Shale to death?

“But your queen’s power isn’t all glamour,” Ivy said. “There has to be some spell she knows that can help me stop Betony and save Hew and the others.”

Thorn shrugged. “There’s spell-fire, I suppose, but it doesn’t really burn either, just shocks you a bit. Unless you’re using dark magic.”

Gillian Menadue had used dark magic to create the Claybane, and a few old piskey tales mentioned dark spells in passing. But Ivy still wasn’t sure she understood. “What’s the difference?”

“Dark magic’s what you use to seriously hurt someone, or change them against their will. I don’t know how it’s done, and I don’t want to, but it’s what the Empress did. That’s why everyone was so afraid of her.”

“I see,” said Ivy slowly. It didn’t surprise her to find out her aunt was using dark magic, but it made her wonder how Betony had learned it. “So this spell-fire you were talking about . . . could you show me?”

Thorn shook her head. “Can’t do it myself, let alone teach you.”

“Fine,” said Ivy, suppressing her impatience, “but maybe Queen Valerian could. And how will I know, if I can’t get in to see her? I can’t just march up to the Oak and demand an audience, can I?”

“Not with all those dratted wards, you can’t.” Thorn thumped her fist into her palm. “Wither and gall! Why does everything have to happen to me upside down and backward?”

“We could make ourselves invisible,” Ivy said, trying not to sound overeager. She could tell Thorn was softening, but she feared to press her luck too far. “I’m sure the wards won’t kee

p you out, whether the other Oakenfolk can see you or not. We’ll go straight to the queen and leave as soon as I’ve talked to her. No one will ever know.”

“For a little poplar, you’ve got a lot of fluff,” Thorn grumbled, but then she sighed. “Oh, all right.”

Ivy could have hugged the faery woman for sheer relief, but she’d tested Thorn’s patience enough already. She clasped her arm gratefully instead and ran back to the barrow to tell Martin.

When she came up the stairs, however, there was no sign of him. Only Daisy, dragging her wriggling daughter out of the treasure chamber. “Thrift! What have I told you?”

The little piskey wailed and struggled, and the tarnished circlet she’d been wearing clattered to the floor. Pearl, the youngest of the spriggan girls, picked it up and clasped it to her chest, watching her playmate sorrowfully.

Ivy wished Daisy would just let the two of them play together, but she had no time to sort that out now. She checked the food storeroom, then searched all the other chambers, finding several children and a couple of dozing aunties in the process. But Martin and the older spriggan boys were missing, and by the looks of it, Mattock had gone with them.

They were probably out fishing or hunting, which meant they wouldn’t be back for hours. Ivy hurried back to the main cavern to find Fern.

“When you see Matt,” Ivy asked her, “could you give him a message for Martin? Thorn and I are going to the Oak, and we’ll be back as soon as we can.” Not waiting for an answer, she headed for the stairs.

“The Oak?” Mattock’s mother sounded puzzled. “What do you think you’ll find there?”

Ivy glanced back at her, smiling. “Hope.”

Ivy had traveled to the Oakenwyld twice now: the first time to beg the faeries to save her mother’s life, the second to repay them by leading them to Martin. But she’d never guessed there was a hidden entrance until Thorn tugged her beneath the rose hedge and she nearly fell into it. Flustered, Ivy followed the faery woman into an earthy-smelling tunnel, then down an adjoining corridor to the heart of the Oak.

Quicksilver

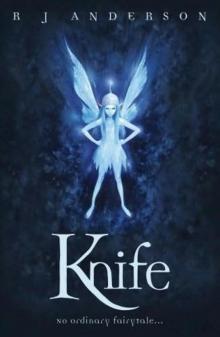

Quicksilver Knife

Knife Arrow

Arrow Ultraviolet

Ultraviolet Wayfarer

Wayfarer A Little Taste of Poison

A Little Taste of Poison Nomad

Nomad Torch

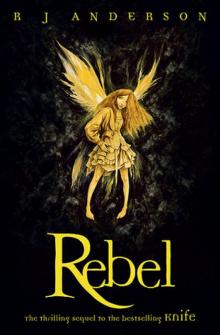

Torch Rebel fr-2

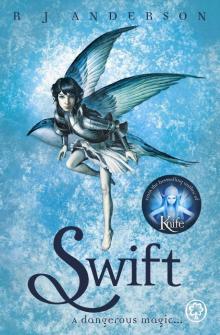

Rebel fr-2 Swift

Swift Faery Rebels

Faery Rebels Spell Hunter fr-1

Spell Hunter fr-1