- Home

- R. J. Anderson

Torch Page 8

Torch Read online

Page 8

One thing was clear, though: whatever happened, Ivy had to keep the barrow a secret. She couldn’t bring her people there unless they gave up their hatred of spriggans, or she’d betray Martin’s trust and put the children in danger as well.

Yet how could she be the Joan of the piskeys and the spriggans at the same time? Especially when one expected her to conjure fire out of nothing, and the other was waiting for her to forge an equally impossible peace?

The sky was darkening when Ivy reached the farmstead. She changed shape in the yard, about to head inside for supper, when she heard the sound of piskeys shouting—and fighting. Heart dropping into her stomach, she raced to the barn.

One glance put her worst fear to rest: there was no sign of Gossan or any of his hunters. It was her own people shaking their fists at one another, while two familiar figures wrestled on the stony floor. Mica—and Mattock?

“Stop it!” Ivy yelled, thrusting her way through the crowd and grabbing Mica by the collar. “What is wrong with you?”

Mica jerked back, swiping sweat-damp hair from his forehead. His eyes were bloodshot with rage. “Tell them!” he snarled. “Tell them he’s lying about you and that—that spriggan!”

Ivy’s bones turned to water. “What?”

“Matt says it’s his filthy hoard that’s paying for us to live here.” He glared at Mattock, who lay winded beneath him with a bloody lip and one eye half-shut. “He says we’ve been all been living off spriggan gold!”

“Living?” Copper scoffed, leaning on his thunder-axe. “Thirty of us crammed into this rabbit hutch, and you call it living?”

“Shut your muzzle, you ungrateful old mole!” Fern swatted him with her dishcloth. “Go back to the Delve and die then, if you’re too fine to make do with the rest of us! And you”—she jabbed a finger at Mica—“stop talking dross about my son!”

Breathe, Ivy reminded herself. Talk to them. “Mica, get off Matt. Who started this?”

Answers poured in from all sides at once. Copper had started it by complaining about his sore back—no, Daisy had done it by using the water Fern had boiled for her laundry—no, it was Mica’s fault for snoring too loud and keeping everyone awake at night—

The only thing clear was that Ivy’s people were unhappy living so close together, especially with the threat of attack putting everyone on edge. And somehow, in all the quarrelling, Mattock had let slip that Martin had given Ivy some treasure.

“All right, yes!” Ivy snapped. “I helped Martin find an old spriggan hoard back in the summer, and he gave me half of the money he got from selling it. Would you rather I’d refused his offer and let you all starve?”

There was a shocked silence while all the piskeys stared at her. Then Teasel said slowly, “But . . . spriggans don’t sell their treasure.”

“Or share it, neither,” said Fern. “Where did you say he—”

“Wait.” Gem held up a hand, his face stony. “You found a hoard with him, you say. So you knew he was a spriggan.”

She didn’t dare look at Mica: she could feel the fury rolling off him in waves. She dropped her gaze to Mattock, whose ears had turned red as his hair.

“I didn’t know when I first met him,” she replied at last, “and he didn’t know it either. His mother was a faery, and he couldn’t remember his father. He’d never even heard of spriggans until a few months ago.”

“But you knew it when you took his treasure.” Mica’s voice was deadly quiet. “And you knew it when . . .”

“I knew it when I brought him into the barn,” Ivy cut in quickly. If Mica told the piskeys she was in love with Martin, it would all be over. “But I also believed I could trust him not to hurt any of you. And I was right.”

Hew shook his head. “This time, maybe. But mark me, that spriggan won’t keep his oath, any more than he’ll let you keep his treasure. He’ll come back, and we’ll all pay for it.”

“Leave that to me,” Ivy said. “It was my bargain, not yours. And even if I banished him, Martin owes me his life.”

“Ayes, but you owed him yours first,” Feldspar spoke up. “You told us he healed you.”

Ivy wanted to bang her head against the wall, but she forced herself to patience. “Yes, but he still owes me more than I owe him.” Or at least she thought so. After all she and Martin had been through together, she’d stopped keeping track.

“In any case,” she added briskly, “it’s done, and there’s no use arguing. The question is, what now? I know this barn’s too small for us, which is why I’m searching for something better. But I can’t do that if this kind of nonsense happens every time I leave you alone. Don’t we have enough enemies without fighting each other as well?”

The piskeys stared at the floor, mouths sullen. Ivy was about to give up and order them back to their duties when Hew cleared his throat.

“What we need’s a good Jack,” he said. “A strong fellow with a level head and a loyal heart to keep the peace and make sure everyone gets what’s owed them. Someone who can be here when you’re not and do as you’d want things done. Wouldn’t you say so, boys?”

The tension eased out of the men’s faces, and they nodded. Mica’s black eyes met Ivy’s, gleaming, and she drew a sharp breath—but he spoke first. “I say we choose Matt.”

Mattock rounded on him, indignant, but Mica gave him a shove. “Shut up. We’ll sort that out later. The point is,” he went on, raising his voice, “Matt already offered for Ivy’s hand, not long ago. Isn’t that right, Ivy?”

She was going to murder Mica. In his sleep, with a dull knife. “Not exactly,” she shot back. “He was thinking about it, but then he changed his mind. Didn’t you, Mattock?”

Matt swallowed. “I did.”

Good, Ivy thought. If he kept his answers vague, there was still a chance they’d get out of this.

“But . . . I’d offer again, if I thought there was any hope she’d have me.”

Ivy shut her eyes, despairing. He was going to tell them she’d turned him down for Martin, and then none of their people would ever trust her again.

“And maybe she would, if I proved myself as brave as she is. I’m willing to wait and see, if she’s willing to give me a chance.”

Ivy’s eyes flew open. Was he saying he’d be her Jack without expecting her to marry him?

If so, it could be the perfect solution. Because much as Mica annoyed her, he wasn’t wrong about Mattock being the best choice. There were a few older piskey-men who were thoughtful and steady, but they were married, and the Jack’s first loyalty had to be to the Joan. He was her chief advisor, her lieutenant, her partner in all things; it made no sense for him to be anything less than her consort—or on rare occasions, her brother. But even Mica knew better than to offer himself as a candidate.

“Will you, Ivy?” Mattock held out his hand to her. “Give me time to show I’m worthy, and then decide if you’re willing to marry me?”

“I’m only seventeen,” Ivy stammered. “I’m too young to get married.”

“But not for a betrothal, surely,” Daisy spoke up, bright with eagerness. She tucked her arm into Gem’s and squeezed it. “We were betrothed at your age.”

“But . . .” It made Ivy sick to say it, knowing how it would hurt him. But she couldn’t give her people false hope. “I don’t love Mattock that way.”

Hew chuckled. “Ah, maid, love’s a choice, not some girlish fancy. You’ve been friendly with the boy since you could walk, and it’s plain to all of us he’d make you a fine husband, even if it’s not yet plain to you. And whatever you think you don’t feel now, there’s no saying you won’t feel it later.”

“But even if you don’t,” Mica cut in, “you’re the Joan, and you have to choose a Jack soon. Or folk will wonder.”

And you’ll have to tell them, of course, Ivy thought resentfully. He’d trapped her, with no more pity than a rockfall blocking up a stope.

“Let her alone, Mica,” Mattock warned. “She needs time to think ab

out it. Clear off, all of you.”

Somehow he managed to make it sound like a request, rather than an order. Dutifully the piskeys retreated—even Mica, though Yarrow had to tug his sleeve, and he obeyed with ill grace. Matt gestured to the barn door, and reluctantly Ivy followed him outside.

“Now,” he said, turning to her, “this isn’t what either of us wanted, but we’ve got to make the best of it. I know how you feel about the spri—I mean Martin, and I know he loves you back . . .”

Ivy’s head jerked up, and Mattock gave a rueful smile. “I’m not such a slag-wit as you think, Ivy. You think I could watch him kneel at your feet, look up at you with his whole heart in his eyes, and not know? Whatever Mica and the others say, I don’t think you were wrong to trust him with your life. It’s the rest of our lives I’m not sure about.”

“He would never,” Ivy said hotly, but Matt put a hand on her shoulder.

“It doesn’t matter. Even if he hates the whole piskey race now, he can’t hurt us without hurting you, so he won’t do it. I know that. Will you please stop trying to fight me? I’m on your side.”

His square, handsome face held no hint of malice, and Ivy’s resistance crumbled. “That’s . . . good,” she said. “But what do you want me to do?”

“I’ll be your Jack, or at least I’ll do the work of one, but I won’t ask you to marry me. Not until I’ve defeated Gossan—”

Ivy clutched his arm. “Matt, no! You can’t put yourself in that kind of danger!”

“I didn’t say I was going to march to the Delve and challenge him,” Mattock explained patiently. “I mean if he comes to attack us, I’ll fight him then. Jack to Jack.”

Ivy was silent.

“You don’t think I can beat him? I only let Mica hit me because I was furious at myself for blabbing about the treasure. If I’d fought back I could have tied him in knots, and everyone knows it.” His mouth twisted. “Except you, apparently.”

“It’s not that.” Mattock was bigger than Gossan, which no doubt did make him stronger. But Betony’s consort was more experienced at fighting, more skilled at magic—and from what she’d seen, far more ready to kill. “I just don’t think it’s a good idea.”

“Look, if I can’t beat Gossan, I don’t deserve to be your Jack anyway. Somebody’s going to have to fight him, just as you’re going to have to fight Betony.” He gripped her shoulder. “You know that, don’t you? Win or lose, it’s the only chance we’ve got to free our people. All our people.”

Much as Ivy dreaded it, he was right. She still hoped it wouldn’t come to that, especially since she didn’t know how to fight Betony without getting burned to ashes. But she’d have to confront her aunt at some point, and when that time came, she’d need a strong Jack beside her.

This wasn’t about her feelings, or Martin’s, or Mattock’s. It was about doing what had to be done.

“All right,” she told Mattock quietly. “I’ll make you my Jack O’Lantern.”

When Ivy announced that Mattock would be their new Jack, the piskeys cheered up at once. Hew clapped Matt on the shoulder, with a knowing wink that made his ears redden, and even Copper stopped complaining long enough to agree it was a fine thing. Then Daisy and Feldspar’s wife Clover rushed to Ivy, eagerly asking what food she wanted for the betrothal feast and what she planned to wear. Ivy cast Matt a desperate look, and as he cleared his throat, all the piskeys came to attention.

“It’s an honor to serve as your Jack,” he said. “But that’s all I’m doing for now. Ivy’s risked her own life more than once to save us, and I don’t blame her for wanting a man who’s not afraid to do the same. So I’m not asking her to marry me until I’ve beaten Gossan in fair combat, and taken his cap for my own.”

Mica folded his arms, his expression skeptical. “And when’s that going to be, exactly?”

“As soon as I get the chance,” Matt told him. “I’m not fool enough to try and best him on his own ground, but he’ll come at us when he’s ready. And then I’ll be ready, too.”

He spoke boldly, but the other piskeys traded dubious looks. They’d never had a Jack who wasn’t bound to the Joan before, and they didn’t like it.

“That’s well enough if he comes soon,” Gem said. “But we can’t sit about forever waiting for that rock to fall. And if Ivy’s so unsure of you that she thinks you need proving—”

“I’m not!” Ivy protested. If she lost her people’s confidence that was one thing, but she couldn’t bear to see them lose faith in Matt.

“Then there’s no reason not to accept him right now, is there?” Mica raised his eyebrows at her. “Unless there’s someone you like better . . .”

It was a challenge, and Ivy had to answer it. “No,” she said flatly. “There’s no piskey I like better than Mattock, and none more fit to be Jack. But I won’t be bullied, Mica. Either you accept my decisions even if you don’t like them, or you can go back to the Delve and take your chances with Betony.”

Mica’s smile froze, and Hew sucked a breath through his teeth. There was a charged silence as Ivy and her brother glared at each other. Finally Mica shrugged. “You’re the Joan.”

Ivy let out her breath. She’d won that round—but Mica wasn’t the only one she needed to convince. Her people had good reason to wonder what their Joan was thinking, and unless she put their fears to rest, there’d be trouble not only for her, but for Martin.

“Give me six months,” she told them. “I’ll be eighteen come spring. If all goes well, we can be betrothed at Midsummer.”

She waited hopefully, but the piskeys only looked glum until Hew stepped forward, pulling off his cap. “Meaning no disrespect, maid,” he said, “but six weeks is enough, surely? It’s only betrothal, not a wedding, and as Daisy’s said, there’s been plenty of folk pledged younger.”

“Hew’s right,” said Teasel. “You might not be ready now, but if you can’t see Mattock’s worth by then, you never will.”

Six weeks was a pitiably short time to beat Betony and Gossan, and find her people a new home. If Ivy could only convince them to make peace with Martin and the spriggans. . . but there seemed little hope of that, either.

“Fair enough,” Ivy said, trying to sound gracious rather than defeated. “Six weeks, then.”

The sky outside the barn was black and starless, and an icy wind swirled across the cobbles. With leaden feet Ivy climbed the steps to the house and went in.

“You look like I feel,” remarked Thorn, striding into the kitchen and reaching to fill the kettle. “I’m having a baby, what’s your excuse?”

Ivy hesitated. She longed to pour her heart out to someone, but she’d asked so much of the faeries already—and she wasn’t sure Thorn would understand. “It’s been a long day,” she replied at last. “Where’s Broch?”

“Well, now, that’s an interesting story. Seems he got tired of waiting for you to tell him what Martin was worked up about, so he went to look for himself.”

Ivy tensed, then relaxed again. He could only have gone to the quoit, after all, and when he didn’t find Martin there he’d surely have given up . . .

“You are in a fine heap of owl pellets, aren’t you?” Thorn said. “A barn full of piskeys and a barrow full of spri—” She caught Ivy’s wrist, scowling. “What d’you think you’re doing?”

She’d tried to clap a hand over the faery woman’s mouth, terrified Cicely would hear. But Thorn’s grip was like iron, and she clearly didn’t like being touched. “Don’t,” Ivy whispered frantically. “Not another word.”

Thorn looked suspicious, but she let go. Ivy tiptoed through the sitting room, where Broch was dozing on the sofa, and leaned down the corridor. The light was on in Cicely’s room, but her door was shut.

“All right,” Ivy said as she returned to the kitchen, “tell me, but quietly. How did he find them?”

“Martin found him first, as it happens.” Thorn’s mouth curled. “He was babbling nonsense, and Broch thought he was drunk.”

“Only the outside. But . . .” Thorn eyed the electric kettle, then poked it on and snatched her hand back as though it might bite her. “They struck a bargain I’m none too pleased about. He wants Broch to go to London and sell some treasure for him.”

Of course. With thirty-one hungry spriggans to feed, the barrow’s stores wouldn’t last forever. And Martin was too shrewd not to make use of Broch while he could. “Sell it how?”

“That’s what I’d like to know,” said Thorn. “Broch’s never been to a big city, and he knows even less about humans than I do. He’ll stick out like a fish in a tree.”

That was the least of the problem. Ivy knew only one shop in London that bought old coins and jewelry, and she was quite certain Thom Pendennis wanted nothing to do with spriggan treasure ever again. “But he agreed? What did Martin offer him?”

Thorn threw up her hands. “Who knows? He kept dodging the question when I asked. Which means it’s probably a lot of broken pottery, or bits of parchment, or some such rubbish. Broch can’t get enough of that kind of thing.”

Distracted, Ivy picked up the tea canister, only to find it empty. She was about to add shopping to her growing list of duties when she remembered she had a Jack now. Mattock didn’t know Truro like he’d known Redruth, but he was used to dealing with humans: he could easily buy all the provisions their people needed. Though it would go a lot faster if he’d let Ivy teach him to travel by magic, instead of tramping an hour through the countryside each way . . .

“Anyway,” said Thorn, breaking into her thoughts, “if you’ve got any advice for Broch, he could certainly use it. If he makes an egg of himself and gets locked up by the humans for his trouble, it won’t be much good to any of us.”

“It’s good to know my wife has such confidence in me,” said Broch dryly from the front room, and the sofa creaked as he got up. “It’s not that difficult, Thorn. I’ll just ask Timothy.”

Quicksilver

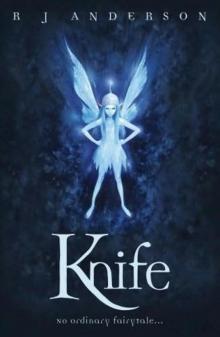

Quicksilver Knife

Knife Arrow

Arrow Ultraviolet

Ultraviolet Wayfarer

Wayfarer A Little Taste of Poison

A Little Taste of Poison Nomad

Nomad Torch

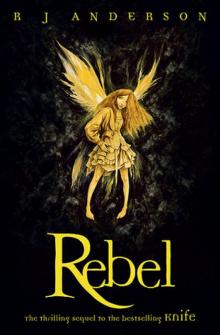

Torch Rebel fr-2

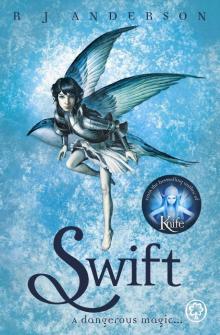

Rebel fr-2 Swift

Swift Faery Rebels

Faery Rebels Spell Hunter fr-1

Spell Hunter fr-1