- Home

- R. J. Anderson

Torch Page 12

Torch Read online

Page 12

Broch gripped Matt’s shoulder until the piskey went limp, then got up and strode to the inner door. “I’ve put him to sleep,” he called. “It’s time.”

The door opened, and Martin walked in. His gaze met Ivy’s, his mouth quirked—and she hugged herself tight, because it felt like her heart was trying to burst from her chest and fly to him. She backed away, struggling to master her feelings.

She’d told Cicely she would give Martin up, and a few hours ago she’d thought herself ready to do it. But how could Ivy forget the bond they’d forged between them? They’d broken tradition and defied prejudice to work together, heal each other, and share thoughts too intimate for words. No matter how much she owed Matt or how hard she might try to love him, her heart and soul would always belong to Martin.

She even sensed what he was feeling right now, though his face showed no sign of emotion. As he drew the knife from his belt and passed a hand over the blade to spell it clean, he was fighting a rush of hateful memories, remembering the lives he’d taken for the Empress. Watching Broch unwrap Mattock’s injured hand sickened him, and it was taking all his courage not to drop the knife and bolt.

Yet he didn’t flinch, or even look away, until Broch said, “Ivy, I need an anchor.”

She’d been there when Broch healed her mother, so she knew what he wanted. Deep healing could be dangerous without someone to remind the healer where his own magic ended and his patient’s began. With an effort Ivy pulled herself upright and put her hand on Broch’s shoulder.

“I’m ready,” she said.

Ivy couldn’t watch the surgery—it was too awful. She kept her eyes shut, grateful for the spell of silence that kept her from having to hear what Broch and Martin were doing. But Broch healed Matt’s wound without a trace of scarring; he even managed to save the thumb, since the thunder-axe had only grazed it. When he finished it looked as though Mattock had been born without those fingers, much as Ivy had been born without wings.

“Let him sleep until morning,” said Broch, sounding dull with weariness. “I’ll come back and see him then.” He made a feeble effort to get up, but Martin stopped him.

“If you try to leap now, you’ll end up in the ocean. You sleep. Thorn will be all right.”

Broch didn’t protest. He dragged a blanket off the nearby pile, rolled himself up in it, and closed his eyes. Martin watched him a moment, then turned to Ivy.

“Are you all right? That was . . . unpleasant.”

She couldn’t speak to him, not with Matt lying there. She could only stare at her shoes until Martin took her arm and drew her out to the main cavern.

The spriggan boys sat up, eager for news, but Martin waved a dismissive hand. “Go to sleep, little groundlings,” he said, and all the hovering lights went out.

There was a chorus of disappointed groans, but to Ivy’s surprise the boys obeyed. Martin led her across to another storeroom, and shut the door behind them.

“Now,” he said, taking a seat on one of the boxes. “Unpack your heart with words, as Hamlet would say. What’s happened?”

Ivy hesitated. How could she burden him with her troubles, when he’d already taken such a huge risk for her sake? Mattock hadn’t seen Martin or the spriggan children, and Ivy hoped to keep it that way, but he’d surely be full of questions about the barrow when he got better. He’d want to know why Ivy had kept it a secret, and how could she satisfy him except by telling him the truth?

“There’s too much,” Ivy said helplessly, sinking down beside Martin. “I don’t know where to start.”

“Well,” said Martin, leaning back, “begin at the beginning, then. All I know is that Broch showed up at the door tonight with your half-dead fiancé and begged me to let him in.”

“So you know about the—” She couldn’t even bring herself to say it. “How?”

“I pried it out of Broch, but it wasn’t all that surprising. I’d guessed your people would want a Jack to go with their Joan, and I knew you’d feel duty-bound to oblige them.” He folded his arms. “He’s a good-looking fellow as piskeys go, and clearly cross-eyed with love for you, so why not?”

He spoke mildly, but there was a tiny, wicked curl at the corner of his mouth, and Ivy smacked him. “You’re why not, and you know it,” she flared—then her face heated as she realized he’d tricked her into giving herself away. If she’d thought she could convince him her feelings had changed, it was too late now.

Martin’s smile deepened. He slid off the box and crouched in front of Ivy, gazing up into her face. “I do know it,” he said. “Which is why I can’t feel anything but sorry for Mattock. Or for you either, so . . .” He took her hands. “You may as well tell me everything.”

In halting words Ivy began to explain all that had happened since they’d last seen each other. But there were so many details, and she was so tired, that by the time she finished it felt like she’d been talking for hours.

“So all that’s left now are women and children, Mica, and a handful of old uncles who can barely stand up to fight. I’ve got seven days to save my people from Betony. And I don’t know what to do.”

She finished in a whisper, her eyes lowered. They were sitting on the floor now, with Ivy’s back against Martin’s chest and his legs framing hers; his arms circled her waist, and he was pressing little meditative kisses into her hair. Somehow he’d coaxed her into his arms while she was talking, but he hadn’t interrupted her; even now he was quiet, his breathing slow with thought.

Ivy waited until she couldn’t bear the suspense any longer, then twisted to look at him. “Well?”

“I need to think,” Martin said. “And you need to sleep.” He brushed his thumb across her cheekbone, leaned forward—and stopped as she shied away. “Still feeling guilty about Mattock, I see.”

“Don’t you?”

Martin cocked his head to one side, considering. “I don’t feel that sorry for him. He made his own choices, Ivy. You didn’t force him to fight Gossan, and you certainly didn’t force him to lose.” He rose, offering a hand to her. “And keeping your distance from me isn’t going to bring his fingers back.”

Ivy gripped his wrist and let him pull her to her feet. “No, but it might make him feel less miserable about losing them. I should go.”

“Your people will be asleep by now.” he told her. “There’s nothing you can do for them tonight.” He walked to the door and opened it. “Come. You can sleep in the girls’ chamber. And by morning, with any luck, Mattock will be well enough to go with you.”

“My lady?”

Ivy stirred and rubbed her eyes, too disoriented to know where she was or how she’d got there. Then it came back to her and she sat up, looking around.

Last night the chamber had been dark, the air thick with drowsy silence. She’d collapsed onto the rug Martin spread out for her, too tired to even cover herself with the blanket, and fell instantly into dreamless sleep. But now glow-spells floated about the ceiling, bathing the room in multicolored light. And she was surrounded by spriggan girls, all gazing at her.

Several of them shared Martin’s pale skin, sharp features, and wiry appearance, and their hair was mostly light like his as well. But a few of the younger ones were nearly as brown as piskeys, while two had a faery-like delicacy that made Ivy wonder who their mothers had been.

“What is it?” Ivy asked, rubbing sleep from her eyes.

The oldest girl bowed, her red-gold hair parting like a waterfall over her shoulders. “Breakfast, my lady,” she said, holding out a wooden bowl.

I’m not your lady, Ivy wanted to protest. She didn’t deserve to lead her own people, let alone anyone else’s. But she didn’t like to make Martin seem foolish by contradicting him, so she gave a wan smile and took the bowl.

Immediately all the other girls jumped up and ran to the main chamber, returning with bowls of their own. It seemed they’d all been waiting for Ivy to eat first—and by the way they dug in with their silver spoons, they were hungry.

The porridge was thick and grainy but sweetened with honey to help it go down. Ivy managed to finish most of it, but the frank stares of the spriggan girls made her self-conscious. Did they think her ugly, with her cropped curls and missing wings?

“I’ll take that, my lady,” said the oldest, as Ivy set the bowl aside. “Did it not please you? Would you like something else?”

“Not at all,” Ivy assured her. “It was a fine breakfast, I’m just full. And please . . . call me Ivy.”

The girls traded uncertain looks. Then the oldest said cautiously, “Ivy.”

Well, at least she hadn’t offended them. “Do you have names? Or do you have to earn them, like the boys?”

One of the smaller girls giggled, and her neighbor shushed her. The oldest gave the two of them a quelling glance, then turned back to Ivy. “Our mothers named us,” she said. “I am called Jewel.”

“Opal,” offered the second oldest, and the others chimed in, “Topaz . . . Diamond . . . Ruby . . .” all the way down to the youngest, Pearl.

Which made sense, now Ivy thought about it: spriggan women not only kept their family’s treasure, they were treated like treasures themselves. Highly prized and closely guarded, they spent their married lives invisible to all but their own husbands, so no one could see the wealth they wore and be tempted to steal it—or them—away.

Still, most of these girls’ names would have been boys’ names in the Delve. Could that be why piskey legend claimed that spriggans had no women of their own?

“I’m glad to meet you,” Ivy said. “And grateful you’ve made me so welcome. It can’t be easy for you having a stranger here, especially one like me.”

“My mam was a piskey,” said Topaz, with a lift of her brown chin. “Ruby’s mam, too.”

Ruby nodded. “But the knocker-men came and took them away.” Her eyes grew dark with memory. “I cried and cried, and I could hear mam crying too. But she never came back.”

So their mothers must have been taken by the spriggans only to be recaptured years later by the piskeys, equally against their will. No wonder Ivy’s people and Martin’s had hated each other.

“The Gray Man’s son told us how he was captured by the piskeys,” Jewel said. “He said he would have died in the false Joan’s dungeon, if you hadn’t come to lead him out. So we trust you. Because you saved him, and he saved us.”

The other girls nodded eagerly, faces shining with admiration. “I’m honored,” Ivy managed to say, though her heart felt bruised. If any harm came to these children because of her, she’d never forgive herself.

“Are you there, Ivy?” Broch’s voice drifted through the doorway, and with a gasp the spriggan girls vanished. She could still hear their shallow breathing, but every one had turned invisible, and the air around them vibrated with dread.

“Don’t be afraid,” Ivy said quickly. “He’s a friend.”

There was a collective exhale, and a few of the girls winked back into visibility, though the rest remained hazy, like nervous ghosts. Ivy got up and followed Broch to the main chamber. “What is it?”

The faery man looked grim. “Mattock’s awake, but his fever’s returned, and I had to heal his hand again this morning. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

“I have,” said Martin, rising to join them. “The first time I healed Ivy, the spell unraveled and I had to do it again. She had a fever, too.”

“That’s true,” Ivy remarked. “I thought it must be something to do with the poison in the Delve.”

“But the second time he healed you, it worked?”

Ivy nodded.

Broch scrubbed a hand through his hair, making it messier than ever. “Then I must be doing something wrong, or there’s more to his injury than we thought. Could Gossan or Betony have put a curse on him?”

Martin started toward the sickroom, but Ivy caught his arm. “You can’t. If Matt sees you—”

“He’ll know I’m here. But since he doesn’t know where here is, does it matter?” He pulled away, and reluctantly Ivy followed.

Mattock lay ashen and sweating on his pallet, head tossing from side to side. His injured hand was swollen, and though his eyelids fluttered, he barely seemed to notice when they came in. But when Martin bent over him, he made a croaking sound and jerked away.

“It’s all right,” Ivy said quickly. “He’s here to help. Will you let him?”

Mattock’s bloodshot eyes slid to hers, searching. Then he gave a little grimace and nodded.

Martin took Ivy’s hand, then reached out to Mattock. The piskey’s jaw clenched, but he held still as Martin closed his eyes in concentration. “His blood’s poisoned,” he said distractedly. “And it’s spreading fast. But I think . . .”

His grip on Ivy’s tightened as green light spread from his outstretched hand, rippling down the length of Mattock’s body. It hovered over him, pulsing gently, then sank into him like water into pumice stone.

Matt groaned and Broch started forward, but Ivy waved him back. “Not yet.” She’d cried out the first time Martin had healed her, too: she’d been so close to death he’d had to practically bully her back to life, and it hurt. But that was a small price to pay for living.

Bilious mist rose from Matt’s skin, snaking in all directions. Martin dropped Ivy’s hand and flung up both his own, lifting the cloud like a blanket and whisking it away. The air cleared, and Mattock relaxed at once. “It’s gone,” he mumbled. “How . . . ?”

Broch stooped to check his temperature, then his pulse. “How indeed,” he said, with a sidelong glance at Martin. “But rest a little longer. We need to be sure the healing will take.”

Mattock struggled up onto his elbows. “I’m hungry.”

“I’ll get you some porridge,” Martin said. He sounded casual, but Ivy could see the weariness in his shoulders.

“Wait.”

Ivy held her breath. Matt was studying his injured hand, turning it back and forth as though seeing it for the first time. He flexed the thumb, rubbing it across the place where his fingers had been. Then he looked up, resolute.

“You saved my life. I owe you a great debt.” His gaze slid to Martin. “All of you.”

Martin paused in the doorway, one hand braced against the arch of stones. “You’re welcome,” he said quietly, and went out.

“It’s extraordinary.” Broch strode into the main chamber, sidestepping the two boys squabbling over the last helping of porridge. “I knew something was wrong with him, I just couldn’t see how to make it right. But you cured Mattock completely. How?”

Martin deftly plucked the ladle from one spriggan boy and the pot from the other, then handed both to a third and scrawnier boy who looked both startled and delighted by his good fortune. “I don’t know what to tell you. Perhaps I’ve just got a knack for healing piskeys.”

“That doesn’t make sense,” said Ivy. “Broch’s been healing my people for weeks.”

“Only injuries,” Broch countered. “Not illnesses. Or infections, either.”

He had a point. Faeries could be wounded but almost never took ill, so there was no need for their healers to learn about such things. Yet Martin had cured Ivy by pure instinct, and now he’d healed Matt the same way. Could it be his spriggan magic, bringing good luck instead of bad for a change?

“Still,” Broch continued, “it would be wise to let Mattock rest a few hours before sending him back to the others. He’ll need all his strength to lead them now. As will you, Ivy.”

Ivy knew he meant it kindly, but his words felt like a mockery. How could she lead her people when they had nowhere to go? And how could Matt protect them with only one hand? Right now he couldn’t even wield a knife, let alone a thunder-axe. And they only had six days left to rescue Hew and the others.

She could feel Martin’s eyes on her, knew that he sensed her turmoil. But he was waiting for the small boy to finish his porridge, and he didn’t speak.

“I must get back to Thorn,” Broch said. “Ar

e you coming, Ivy?”

“Soon,” Ivy promised him, and with a nod the faery man walked out.

“Right,” said Martin briskly. “Caliban, Tybalt, you’re on wash-up.” He handled the pot and ladle back to the boys who’d been arguing; they made sour faces but began collecting the dirty bowls at once. “Hamlet and Horatio, sweep the cavern. The rest of you, roll up your beds. Then we’ll talk.”

The boys seemed not to mind their Shakespearean nicknames, because they all jumped to obey. “You’re good at this,” Ivy murmured, but Martin only smiled.

“I used to work at a hostel in London. It’s not so different.”

Perhaps, but it wasn’t Martin’s housekeeping skills that had impressed her. “I meant being a leader.”

“Only because they’re still young and ignorant enough to be in awe of me. I’m sure it’ll wear off.” He took Ivy’s arm. “But we have things to discuss, before you go back to the others.”

He was leading her back to the room where they’d left Mattock. “Wait,” said Ivy, but Martin’s grip stayed firm.

“I know what I’m doing,” he said. “Or at least I hope so. Let’s talk to your Jack and find out.”

When Ivy left the barrow, she felt dizzy with apprehension. She’d been taken aback when Martin told them his plan, and so had Mattock; they’d both protested that it was too much to accept, and far too great a risk.

Yet he’d been adamant, so what could they do but give in? Even the faint hope Martin offered was better than no hope at all. Steeling herself, Ivy leaped back to her fellow piskeys.

As soon as she materialized, Fern jumped up and rushed to her. “Where’s Mattock? Is he all right?”

Her hair was straggling out of its topknot, her eyes bagged with lack of sleep. Ivy took off her coat and draped it around Fern’s shoulders. “He’s well, and you’ll see him soon,” she promised, leading Matt’s mother back toward the fire.

The other piskeys huddled around the flames, looking equally dirty and exhausted, while Mica turned a rabbit on a makeshift spit and winced as the smoke got in his eyes. Broch sat next to Thorn in the corner, one arm protectively around her; by her dazed expression, she’d been up all night. Outside the shed Cicely stood at human size, petting Dodger’s neck and whispering to him. But she didn’t look up, even when Ivy cleared her throat to speak.

Quicksilver

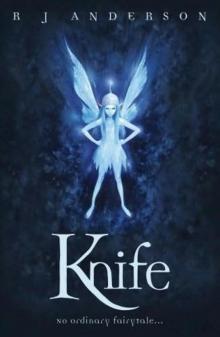

Quicksilver Knife

Knife Arrow

Arrow Ultraviolet

Ultraviolet Wayfarer

Wayfarer A Little Taste of Poison

A Little Taste of Poison Nomad

Nomad Torch

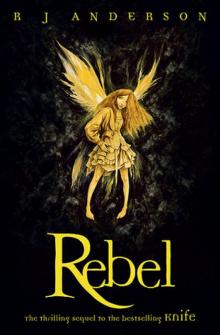

Torch Rebel fr-2

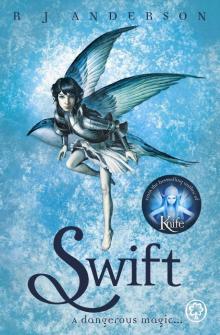

Rebel fr-2 Swift

Swift Faery Rebels

Faery Rebels Spell Hunter fr-1

Spell Hunter fr-1